From Poppy to Coffee : How Thailand Became a Model for Alternative Development

From Poppy to Coffee : How Thailand Became a Model for Alternative Development

วันที่นำเข้าข้อมูล 13 Sep 2021

วันที่ปรับปรุงข้อมูล 30 Nov 2022

When their bright red petals fall away, farmers would slit open the egg-shaped seed pods of Papaver somniferum or opium poppy. Milky ‘poppy tear’ would then ooze out from these open wounds, starting the extraction of the crudest form of opium. This method of poppy cultivation can be traced back to at least five millennia ago in the texts of the Sumerians, who called the plant Hul Gil, or the ‘plant of joy’.

Photos from left to right: poppy heads with seeds (credit: tiborgartner, iStockphoto.com) and close up on Papaver somniferum, the opium poppy cultivation (credit: Lex20, iStockphoto.com)

Photos from left to right: field of poppies blowing in the wind (credit:FabioFilzi, iStockphoto.com), field of pink poppies (credit: ThomasShanahan, iStockphoto.com), and fresh opium poppy field (credit: selikmaksan, iStockphoto.com)

Joy is exactly the reason why this plant spread all over the world so quickly. Originally used for pain relief, opium was later introduced as a recreational drug in Europe and Asia. Highly addictive, it dominated international trade and politics in the 19th century. It was only after World War II that its harmful effects were widely acknowledged and opium suppression became a global agenda.

In Southeast Asia, opium poppies have been cultivated for centuries. Possibly brought in from southern China, the use of opium was integrated into the culture of indigenous communities such as the Hmong and Karen. Their usage of poppy seeds was in moderation and in their traditional medicine and religious ceremonies, and even had been used as a currency.

The arrival of migrants and ethnic groups during the Chinese Civil War in the 1940s led to an exponential increase of opium production in the mountains of Thailand, Myanmar and Lao PDR. As the only available cash crop, the new highlanders had little choice but to cultivate poppy to escape poverty, but even so, did not receive high returns. The network of illegal trade in the Golden Triangle, an area where the borders of the three countries meet, peaked during the 1960s with an estimated 145 tons of opium produced in Thailand annually.

The Thai government banned opium in 1958. However, insufficient resources and the lack of understanding among the highland peoples resulted in an unsuccessful campaign to restrict poppy cultivation. As the locals resented the government’s efforts to resettle them in the lowlands, Thai officials started to look for an alternative method to reduce opium production.

In 1969, while visiting Chiang Mai province, His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej The Great learned that some poppy growers could earn a comparable amount of money from selling local peaches. That was when he developed the idea that growing an improved peach variety could possibly generate more income than opium poppy, minus the risk of being involved in criminal activities, and therefore, opium cultivation could organically wither away from existence.

This concept of crop substitution and genetic improvement was swiftly translated into actions that has created an environment of human security and a sustainable livelihood for villagers -a holistic approach to security. The concept would eventually be called alternative development model, whereby the people are empowered to pursue the development path of their choice rather than being forced to surrender to prevailing conditions. The King deployed his knowledge on geography and botany to sponsor the research on alternative crops. He instituted the ‘Royal Project,’ a private charitable organisation to support alternative development in Northern Thailand. The Royal Project ran its first training programme with the highlanders in 1970, while the King set up development stations in the area.

Photo: Children with strawberries from the Royal Project (Source: Doi Kham website)

In tandem with the Royal Project, members of the Royal Family supported several other initiatives to address illiteracy, poverty and public health in the remote mountains. Many of them were frequent visitors to the villages to organise medical check-ups through the Princess Mother’s Medical Volunteer Foundation, and to provide assistance to schools in need. All these concerted efforts took decades of perseverance to bear fruit. But the yield, as proven today, is worth the wait.

Since the beginning, the Royal Project worked with the Thai government and international organisations to conduct research and development, and to provide seeds, fertilizer, training, and supporting infrastructure. In 1971, the Royal Project and the Thai Narcotics Control Board partnered with the United Nations Fund for Drug Abuse Control (UNFDAC) to establish the Crop Replacement and Community Development Project. Since then, the Royal Project and relevant agencies have introduced more than 150 new crops to poppy growers, including arabica coffee, tea, cabbage, apple, and decorative flowers.

Photo: Flowers from Doi Tung Royal Project (Source: Doi Tung Club Facebook page)

Nevertheless, poppy eradication did not begin until 1985. The officials recognised that radical measures could lead to counterproductive results. They waited until the projects could generate sufficient income for poppy farmers, and eradication was mostly negotiated to ensure a sustainable outcome. As a result, poppy cultivation in Thailand fell by 97 percent from 1985 to 2015 and has never relapsed.

Today, the Royal Project is a public foundation with 39 development centers and research stations. Under the patronage of His Majesty King Maha Vajiralongkorn, the foundation continues to expand its work with the opening of Ler Tor Development Center in Tak province in 2016, which is assisting more than 300 Karen farmers. The Royal Project products are currently processed and distributed in supermarkets under the brand Doi Kham. Some products, such as dried fruit and juice, are available in Japan, China and Russia.

Photo: Doi Kham dehydrated pink guava (Source: Doi Kham website)

Photo: Doi Tung coffee (Source: Doi Tung Club Facebook page)

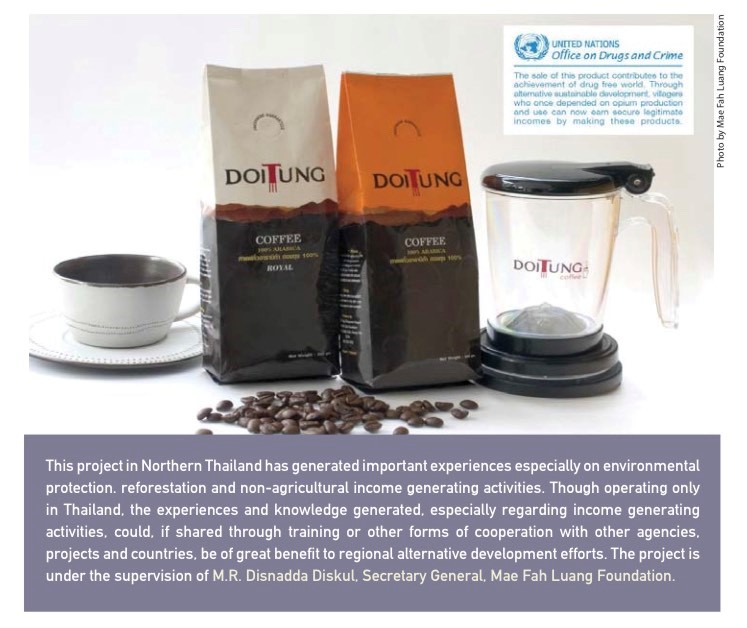

Coffee beans of Doi Tung, another brand of alternative development products from Mae Fah Luang Foundation, created by Princess Srinagarindra, the Princess Mother in Chiang Rai province, has been selected by Japan Airlines and Japanese retailer Muji for their catering service.

The works of the Royal Project were realised through synchronised efforts of all key players. For instance, the Thai government provided human capital development by extending healthcare services and developing schools in former opium-producing villages, as well as the provision of Thai citizenship. The highland communities now have access to rights as a Thai citizen, such as the right to own land, non-farming work and qualifications to apply for bank loans. This would not have been possible had it not been for the monarchy’s subtle but effective support to steer collaboration that has bound all stakeholders together, from policy makers to villagers, towards the same direction. Considering the local villagers’ skepticism of government officials at the time, the face of the institution was the only one that was received with genuine respect and trust by all parties.

Photo: Angkhang Royal Agricultural Station in Chiangmai Province (Source: Office of the Royal Development Projects Board website)

Photo: Angkhang Royal Agricultural Station in Chiangmai Province (Source: Public Relations Department Facebook page)

The Alternative Development model or AD initiated by the Royal Project Foundation has been recognised by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime as a uniquely successful undertaking in sustainably replacing narcotic crops with alternative means to generate income. Not only did the Royal Project contribute to the security-building process by reducing illicit crop and crimes, it also succeeded in bolstering economic, food, and environmental security for the ethnic communities who were living on the edge of poverty. It has since gone the extra mile to collaborate with UN agencies by introducing similar programmes in countries such as Lao PDR, Myanmar, Colombia, Peru and even Afghanistan, to name a few. Aiming to be the learning institute for sustainable development, the Royal Project Foundation continues to empower and dignify the livelihoods of local communities in Thailand and beyond.

Photo: UNODC Eastern Horizons, Summer/ Autumn 2005 edition, page 8

(Source: UNODC website)

* * * * *

About the author

Mr. Chutintorn Gongsakdi is a career diplomat and is currently Deputy Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Thailand. He oversees the Ministry’s multilateral and regional economic diplomacy. His portfolio includes the Asia Cooperation Dialogue, APEC, BIMSTEC, IORA and OECD. Prior to his appointment as Deputy Permanent Secretary, Mr. Gongsakdi served in key positions including Ambassador of Thailand to India, and Director-General at the Department of International Economic Affairs.

Royal Thai Consulate-General, Fukuoka

Monday - Friday (Except Public Holidays)

Morning 9.00 - 12.00

Afternoon 13.30 - 17.30